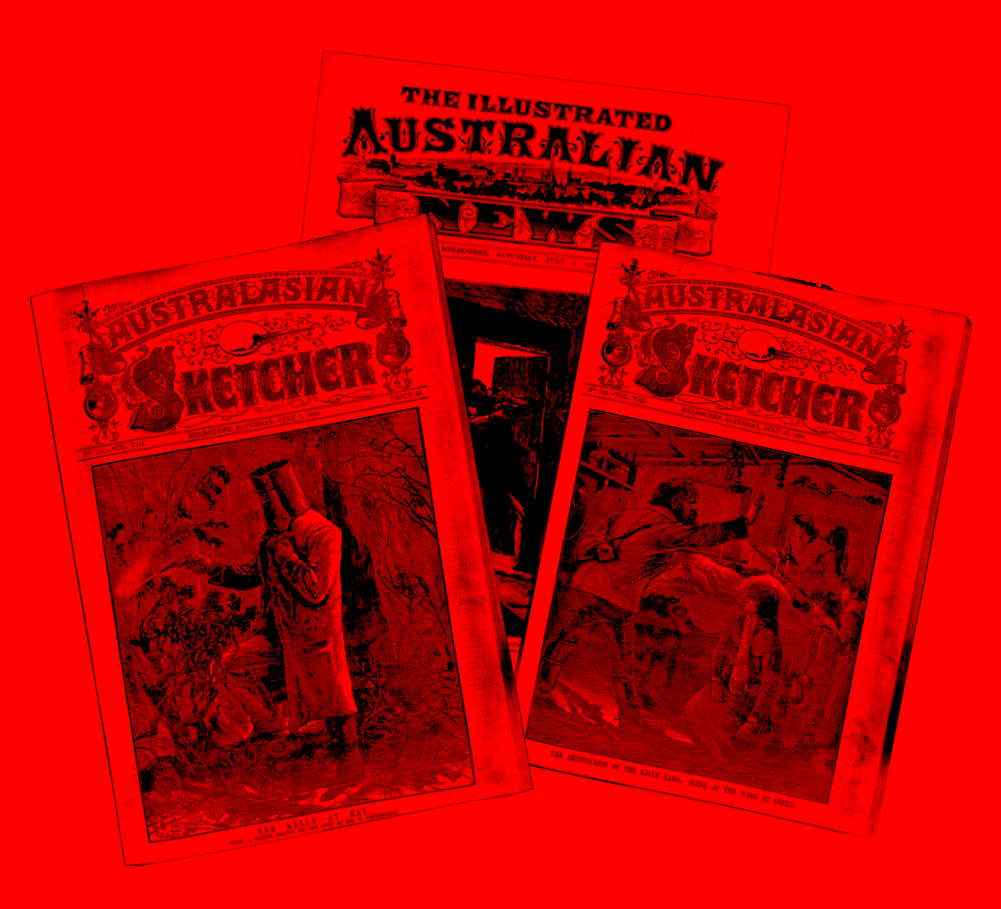

Portland Guardian (Vic. : 1876 – 1953), Thursday 1 July 1880, page 2

SUPERINTENDENT HARE’S STATEMENT.

Superintendent Hare telegraphs as follows:—

“The pilot engine was stopped half a mile from Glenrowan, and we were told that the line had been pulled up by the Kellys a mile beyond Glenrowan. Train and pilot went up to Glenrowan station. I then jumped out of the train and went to the stationmaster’s house. The wife told me everybody in Glenrowan had been taken into the bush by the Kellys. I immediately ordered every man out of the train, and at the same moment Constable Bracken rushed up, saving he had escaped from Jones’ publichouse, ‘And for God’s sake go quickly or they will get away.’ I then ran away, with two or three men following me, and went up to towards Jones’s, and when I got within fifty or eighty yards a shot was fired from the house, and struck me in the left wrist (not seriously.) I immediately got the house surrounded by all the men I had. I have telegraphed for the men from Wangaratta, and Mr. Sadlier, with all available men, is going up at once. Ned Kelly has three bullet wounds in him. Dr. Nicholson does not consider any of them mortal. Police very plucky and game. The armour the gang have on is formed out of ploughshares. Ned Kelly was armed with a breastplate and iron mask and helmet.”

Detailed statements by the several persons more immediately concerned in the affair are given by our Melbourne contemporaries.

John Stanistreet, station-master at Glenrowan, was called out of bed at 3 o’clock on Sunday morning, and his door burst in. The intruder announced himself as Ned Kelly, made a prisoner of Stainistreet, and directed him to remove rails beyond Glenrowan. But line-repairers were got for this work. The station-master was ordered to signal the line safe to the expected special train, or he would be shot. About 17 persons were made prisoners in the railway station house, but all but Stanistreet and his family were soon removed to Jones’ Hotel. Before the train arrived the station-master was taken to Jones’s. Firing there went on furiously.

Robert Gibbons was one of the prisoners in Stanistreet’s house, and in the hotel. Of the scene at the latter place he said:—

Ned and Dan Kelly were walking about the house quite jolly, and Byrne was in charge of the back door, the front door having been locked, the key of which Byrne kept. They continued walking about and drinking, and making themselves quite at home and jolly, till about three o’clock on Monday morning, when Ned Kelly came into the room where we were and told us that we were not to whisper a word of anything that was said there or say anything about him, and if he heard of anyone having done so, he would shoot him. He went to the door of the room and said, “Here she comes,” and with that the gang went out into the back, as if to hold a consultation, and returned in a few minutes, and said that the first man who left the room would be shot. After giving these directions I saw two of the gang, I could not say which, mount their horses and ride away. They came back in about ten minutes’ time. When they came back I saw Dan go into a small room at the back of where we were, with another member of the gang, and in a few minutes they came out with their armour on, and their firearms. When they came out the other two then went in and did the same. The police then arrived and commenced to fire on the place. There were about 40 people in the place at this time, comprising men, women, and children. The women and children commenced to scream and shriek, and Mrs Jones’s girl was shot on the side of the head, and her eldest boy in the side. Directly the firing commenced we all lay down on the floor, because the bullets rattled on the side of the house, and sometimes came through it. We remained in this position till about 10 o’clock, when we all rose and came out, holding up our hand. We were induced to take these steps from hearing the police calling to us to come out. We thought the police were giving their last warning, and so we all rushed out. We left Dan Kelly and Hart and Byrne in the back room, but we could not may how they were. Some of the people said that Byrne was lying dead in one of the back rooms.

Constable Bracken said:— At 11 o’clock on Sunday night a voice, which was strange to me, abruptly called upon me to come out, and wondering what was the matter, I got up and opened the door. As I did so, a tall man, whose face was hidden behind what seemed to be a nail can turned upside down, stepped into the doorway, and pointing a revolver at my head, said, “I’m Ned Kelly; put up your hands.” I said, “You be ——; you are only someone from Benalla sent here to try my pluck.” He said, “Throw up your hands;” and thinking that he was only joking, I put up one hand. He appeared to lose his temper, and putting the pistol close to my face, said, “Throw up both hands; we will have no —— nonsense.” I threw up both my hands, and he pushed me into the house, and followed me in. He took up my rifle and revolver, and asked for the cartridges, but I said that I had not the key of the chest. He then took me out into the stable, and asked me if I had a good horse. When I went outside with Ned Kelly I saw Joe Byrne and Reynolds standing outside, and going into the stable they made me saddle and mount my troop horse. Byrne took the reins and led the animal, and Ned Kelly rode behind, with Reynolds walking at his side. Ned Kelly told me that if I tried to get away he would shoot me and we went off to Jones’s Glenrowan Inn, where I found about twenty or twenty five people hustled together in the bar and sitting room. They did not appear as if placed under constraint, but were at liberty to go into any of the rooms. Steve Hart was at Stanistreet’s, the station-master’s, but the other members of the gang loitered about, with their revolvers and rifles unslung, as if ready for use. When I went in I noticed them lock the front door, and place the key on the end of the bar counter, near the wall, and when they were not noticing, I quietly picked it up and awaited my opportunity, When the train was coming the gang went into one of the back rooms as if to hold a consultation, and I put the key to the door, unnoticed by the crowd, and ran away, jumping the railway fence, and arriving on the station platform just as Superintendent Hare and party were getting under arms. I told them briefly how matters stood, and they charged for the house, while I took one of the horses that had just been saddled and rode as fast as I could to Wangaratta for reinforcements. I warned the party of the line having been broken up, and accompanied them back to the scene and joined with them in the siege that had been made. Mrs. Reardon, wife of a platelayer, working on and living near the line at Glenrowan, made several desperate efforts to escape from the inn during the thickest of the fight with an infant in her arms, calling frantically on God and the police to spare her children. On every occasion that she got out of the house some of the men called her back again and came out after her. This immediately drew the fire of the police on the place, and she was forced to take shelter behind trees, or by falling on the ground. Between 5 and 6 o’clock she made a final effort, and ran in the direction of the station with the bullets falling all round her, and doubtless she would have met with some disaster if it had not been for the brave conduct of the railway guard Dowsett, who rushed boldly into the open when she seemed to be about to waver, and carried her to the train, where she was provided with shelter. Her husband and three children were still in the doomed inn, so her agony and painful excitement may be better imagined than expressed.

Senior-constable Kelly’s narrative contains nothing beyond what has already been given, and neither does Sergeant Steel’s. At 3 o’clock, as there was no prospect of getting the outlaws from the hut, which was now well riddled with bullets, Senior-constable Johnstone of Violet Town, led the forlorn hope, and went boldly up to the hut, and, under cover of a continuous fire from the scouts, lighted the Benalla side of the building, The fire gradually increased and gained upon the matchwood construction, and in five minutes the place was one mass of flame. The hotel continued burning until late in the evening, when, as the fire abated, the bodies of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart could be plainly discernible amidst the flames, roasting and shrivelling up in a horrible manner. It took some time before they were recovered, and then the remains presented such a sickening and revolting appearance as almost to turn one’s head with horror. The limbs and bodies were swelled and twisted out of all shape, the leg of one had been broken, and a foot burned off, while there was hardly a semblance of fingers on either. The features were perfectly unrecognisable, and it was only by the difference in the shape of their heads that the friends of either were able to identify them. The bodies were taken out of the fire, laid on a sheet of bark, and brought to the railway station, where, in the broad day-light, they lay exposed to the view of the public for a long time, in all their horrid blackness and ghastliness. Mrs. Skillion and the younger sisters of the Kellys went to look on all that was left of their brother Dan. It was a heartrending sight, and one never to be effaced from the memory, when they knelt down amongst the crowd on the platform and gave vent to their grief in bitter wails and tears. Byrne was quite stiff when taken out, and had apparently been dead for some time. He was dressed in dark striped trousers, dark striped shirt, and blue sac coat. On one of the fingers of his right hand he wore the topaz ring which was taken from Constable Scanlan after he had been shot by the gang, and on the fourth finger of his left hand was also another gold ring, with a large white seal in it. In one pocket a Roman Catholic prayer book was found, together with some cartridges, and in another a small brown paper parcel, labelled “poison,” and several bullets. Immense crowds came from Benalla, Beechworth, and even Wodonga, to view the scene, and the police had great difficulty in keeping the people from rushing the room where Ned Kelly lay wounded.

Father Gibney, of Perth, Western Australia, who is on a visit to the district, is most attentive in administering religious consolation to the outlaw. Further attempts proved useless to extract any information from him relative to what had become of Sergeant Kennedy’s watch. From the position in which the bodies of Hart and Dan Kelly were found, and their closeness in the fire, it is assumed by some that they shot each other after being wounded. At any rate, they were divested of their helmets and breast plates, which weighed nearly 100lb. each (Ned Kelly’s weighed 120lb.), while in the case of Byrne his helmet was attached to him when dragged out of the burning building. A propos of this it would appear that the outlaws had been dead some time before the house was set on fire, as Father Gibney, who courageously, and amidst the cheers of the crowd, rushed up to the blazing house and got inside, informs me that when he caught up the nearest man to him, (Byrne), and attempted to carry him out, he saw the other bodies lying together farther in the room. Several brave and determined attempts were made by the police and bystanders — who, regardless of the chance of being shot down, crowded around the building — to try and save the inmates from the front of the house, while the back was rushed by in eager throng of officers and men, who, revolver in hand, determined to conquer or die, dashed into the building in order to discover if any of the outlaws still lived. The terrible flames, however, and the thick volumes of smoke drove them back, and in a few moments nothing could be seen of what was once the inside of the hotel. When the flames abated, the bodies of the outlaws, together with a dog, which had also been burnt to death, were dragged out of the fire, and in the detached kitchen the unfortunate platelayer Cherry was found in a dying condition, and breathed his last very shortly after being brought out of the building. It should be mentioned that previous to the building being fired, repeated overtures were made to Inspector Sadlier by the men under his command to storm the building, but unwilling to run the chance of the loss of life Mr Sadlier refused, trusting to capture the outlaws by some less risky method. After lying on the railway platform till the train came in, the bodies of Hart and Dan Kelly were laid on a stretcher, covered with a cloth, and placed in the train. Byrne’s was similarly treated, and then Ned Kelly was carried on a stretcher, and placed also in the same carriage.

The Argus of yesterday has the following:— The tragic encounter with the Kelly gang at Glenrowan was again the leading topic on Tuesday. The surviving outlaw, Ned Kelly, was brought to town from Benalla by the afternoon train, and crowds assembled both at the Spencer street and North Melbourne stations to await his arrival. He was taken out at the latter station and conveyed to the Melbourne gaol. The reports of Dr. Charles Ryan, who accompanied him on the journey, and Dr. Shields, the medical officer of the gaol, are to the effect that, though rather severely wounded, Kelly will, in all probability, recover from his injuries. The wound of Superintendent Hare, who returned to Melbourne on Tuesday, is severe, and may cause permanent stiffness of the wrist, but Mr. Hare, on the whole, is doing very well. It is with regret that we record another death arising out of the fray — that of the young lad, son of Mrs. Jones, who kept the hotel in which the bushrangers met their fate. It is also reported that the boy Reardon, son of the platelayer, is in a dangerous condition. A magisterial inquiry was held at Benalla on the remains of Byrne on Tuesday, when the finding was that the deceased had been shot by the police in the execution of their duty.