Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895 – 1930), Sunday 27 June 1920, page 19

Note: This article is rife with factual errors and is presented to demonstrate the way in which many of the falsehoods around the Kelly story were perpetuated in the early 20th century. Often newspapers would publish accounts like this without doing any fact checking, relying solely on the assumption that the person claiming to have this esoteric knowledge about the outlaws was trustworthy. This is partly how the myths about Dan and Steve surviving the siege were popularised and perpetuated. — AP

Untold Reminiscences of Ned Kelly’s gang

THE START AND FINISH OF “FLASH,” MISGUIDED YOUTHS

——◇——

Contamination of Environment and Sympathy of Evil Minds Lead the Kelly Gang to Death

————

To-morrow will be the fortieth anniversary of the capture of Ned Kelly, the notorious bushranger, at Glenrowan. The accompanying pictures and narrative have been supplied to us by Mr. W. R. Wilson, of Sydney, who has a wonderful store of knowledge of the doings of the gang. At Wangaratta Mr. Wilson was a school-fellow of Ned Kelly and two of the other outlaws, and he was present at the capture of the chief ‘ranger. So much romance has been woven round the career of the Kelly gang that Mr. Wilson feels impelled to tell the true story as he knows it.

To-morrow, June 28, is the 40th anniversary of the date of the closing episode of the sensational career of the notorious Kelly gang of bushrangers, whose daring exploits of murder and plundering during the 26 months they defied the efforts of both the Victorian and N.S.W. police to effect their capture, caused world-wide interest.

School Days of the Outlaws.

The romance of the Kelly Gang will last as long as Australia itself. His name will live longer in the annals of Australian history than that of many much more worthy men.

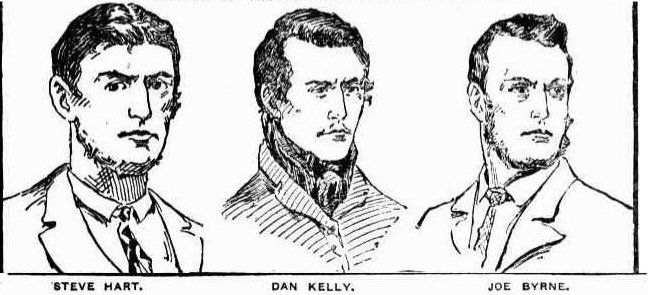

On the 28th June, 1880, the Kelly Gang of outlaws, consisting of Steve Hart, Joe Byrne and Dan Kelly, under the leadership of Ned Kelly, after committing a series of bushranging outrages, then unparalleled in the history of the Colonies, were done for at Glenrowan, a small Victorian township, about 50 miles from the N.S. Wales border, on the Sydney-Melbourne railway line.

After a siege extending over 14 hours, Ned Kelly was captured wounded, and was, after trial, hanged.

Three of his companions met their death the same day at the hands of the besieging party of police, black trackers, and civilians numbering over 70, who afterwards participated in the reward of £8000 jointly provided by the Victorian and N.S.W. Governments.

The contributor of these memoirs was a schoolmate of three of the outlaws at Wangaratta nearly half a century ago, was an eye-witness of their capture, was familiarly acquainted with many others who figured conspicuously in the drama, and is in a position to record an authentic account of the stirring events of these men’s lives. The writer feels impelled to write these memoirs as a protest against the many “faked” stories and plays of the gang’s exploits.

Ned Kelly as a Boy.

The writer first remembers Ned Kelly as a lad of 11 or 12 years old attending the Roman Catholic school at Wangaratta. Ned, in those days, was brown-haired with bright blue eyes, sturdy, reckless and daring, and possessed, even at that period, a somewhat magnetic personality which won for him the confidence of his less daring schoolmates when raids on orchards and Chinese watermelon patches were to be made.

Among the scholars attending another school in the town was a lad of humble parentage, afterwards destined to achieve distinction as the first Australian-born commandant of the Commonwealth Military Forces — the late Major-General J. C. Hoad. He and Ned Kelly had many a bitter fight over the ownership of a derelict, ownerless billy-goat. In turn the goat was captured and re-captured by the rival boys of both schools led by Kelly and Hoad. One day the local policeman intervened with a shotgun. That was the end of the billy goat and the vendetta. The best of friendship afterwards prevailed between the youthful leaders, and the peace-making policeman became the common enemy of both.

Family History.

Ned Kelly and his brothers were the sons of John Kelly, who was transported to Australia in 1841 from Tipperary, Ireland. He married a Miss Quinn and took up a small selection at Wallan Wallan, Victoria, where Ned was born in 1853. Four other children were born, viz., Ellen (afterwards Mrs. Gunn, since deceased), Mary (afterwards Mrs. Skillion, since deceased), Jim and Kate (deceased). Kate afterwards achieved notoriety in connection with the assistance she was known to render to the family of bushrangers.

John Kelly, the father, was later awarded with a five years’ imprisonment for cattle stealing. Shortly after his release from Kilmore goal, in 1865, the family removed to Three-mile Creek, near Wangaratta, where the two youngest members of the family, Dan and a sister named Grace were born. Some years later John Kelly took up a selection at Eleven-mile Creek, near Greta, in the vicinity of other selections held by his brothers-in-law, Quinn and Lloyd, in the midst of a desolate, unsettled, mountainous country.

The district had previously become notorious as the scene of the depredations of the notorious bushranger Daniel Morgan (who was shot at Peechelba Station in April, 1865) and of Dan Power, who was captured by a party of police under Inspector Montgood at Bongamera Station, King River, in 1870.

Ned Not a Police Guide.

In connection with the latter’s arrest it was stated at the time that the police party was directed to Power’s hiding place by Ned Kelly, then a boy of 16, in the disguise of a black tracker, for the sake of the £500 offered for Power’s capture.

In justice to Ned the writer believes this suspicion to be absolutely without foundation, the real informant being a member of another branch of the family, long since deceased. As a matter of fact, Ned was at that time a trusted friend and ally of Power’s, and kept him well posted as to the movements of the police.

The Wangaratta district at that period had an unenviable reputation for cattle duffing and horse stealing, and among a certain class of residents the crimes seemed to meet with approval and encouragement.

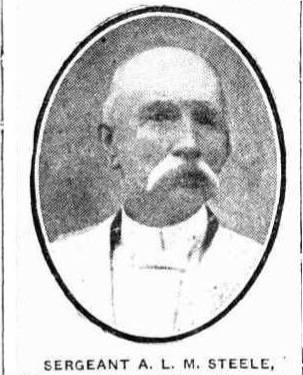

The name of young Ned Kelly soon became associated with those openly suspected, and owing to the vigilance of Sergeant Steele, a shrewd, zealous officer, who had been recently placed in charge of the district, he was at the age of 17 convicted and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for “receiving” a stolen horse. The effect of the sentence increased an inherent bitter hatred of the police in the lad’s heart, and he swore to be avenged for what he considered an unjust and undeserved sentence. Ned declared that the culprit was a local character known as Wild Wright, who, together with James Kelly (Ned’s brother), subsequently received a long sentence on another charge of horse stealing.

Ned Commences Business.

Ned Kelly soon became to be looked upon as leader of a well-organised gang of stock marauders, who operated with great success on both sides of the Murray river in N.S.W. and Victoria.

On reaching manhood he had developed into a tall, well-set-up athletic young man, with a dark brown beard, aquiline nose, bright, flashing blue eyes, and pleasing personality. He was frequently to be seen at race meetings, sports gatherings, or country dances, accompanied by other young men of what was then known as the bush larrikin type.

Ned was always well mounted, flashly attired, after the style of the bushmen of those days. His mother’s home at Eleven Mile Creek soon became to be known as the rendezvous of suspected cattle-duffers and other shady customers, and was constantly under police surveillance.

About this time Steve Hart and Joe Byrne were sentenced to six months for “illegally using” horses belonging to neighboring squatters, and Dan Kelly got three months for pillaging a hawker’s waggon; but Sergeant Steele, despite his untiring zeal, could not get a case against Ned, although the latter subsequently confessed to being instrumental in stealing as many as 280 horses In one year and sending them to N.S.W. for disposal by accomplices on that side of the border.

Steve Hart on the Job.

Steve Hart, the second son of a respectable family of settlers at Wangaratta, was a proud-spirited, athletic lad, who took his sentence very much to heart, and on his discharge from gaol was heard to declare his anxiety to start out bushranging if he could get a suitable mate to join him, and have “a short life and a merry one.”

All these young men were noted for their marksmanship, horsemanship, and knowledge of the country, the fastnesses of which provided excellent cover for stolen stock. Their accomplices on the N.S.W. side of the river co-operated with them in transferring “lifted” horses and cattle to Victoria in exchange for those stolen on the Victorian side, and so many were engaged in the traffic, and so perfect in detail were the methods adopted that the crime merged into a recognised industry, which the police seemed powerless to check.

Eventually the vigilance of Sergeant Steele, of Wangaratta, was rewarded, and this brought about the beginning of the end. A valuable mare had been stolen from one Kennedy, a resident of Oxley, ten miles from Wangaratta, and Sergeant Steele traced the animal to the possession of Dan Kelly and Jack Lloyd, who had disposed of her to a resident of Porpunkyah, just over the Murray. With the assistance of the black-trackers, sufficient evidence was obtained to justify the arrest of the two men named, and with that object in view Constable Fitzpatrick, with a warrant, visited Mrs. Kelly’s hut at Eleven Mile Creek on April 15, 1878.

The story of what occurred on that occasion materially differs. Fitzpatrick alleged that he was attacked and assaulted by Mrs. Kelly, her son-in-law, Jas. Skillion, and a man named Williamson, who was present, and who was afterwards, shot in the wrist by Ned Kelly in his attempt to bring about the arrest of Dan Kelly. Against that it was alleged that the constable brought the assault upon himself through an alleged impropriety towards Kate Kelly, then an attractive girl of about 18.

At all events, upon the constable returning to Benalla and reporting the incident, a party of police was despatched to effect the arrest of all concerned in the alleged assault. The police arrested Mrs. Kelly, Skillion, and Williamson, but Ned and Dan Kelly were not about the place.

Mrs. Kelly, Skillion, and Williamson each received long sentences for their part in the alleged assault, and the severity of the punishment was, at the time, adversely commented upon. It was freely said that the sentence was greatly responsible for the subsequent developments that took place, popular sympathy being against the constable, who was known to bear a very indifferent character, and was subsequently discharged from the police by a commission appointed to inquire into the matter. The same commission concurred in the belief that “the incident formed one of the many causes that assisted to bring about the Kelly outrages.”

Jack Lloyd, who was implicated in the alleged case against Dan Kelly, was acquitted. The commission, however, sought to make it clear that there was no evidence to support the suggestion that the police had persecuted the Kelly family and their relatives. Constable Fitzpatrick’s conduct, “however justified by the rules of the service,” was “considered by the commission as being unfortunate in its results.”

The Wombat Ranges Episode.

After the initial episode above related and the conviction of Mrs. Kelly, Williamson, and Skillion, nothing more was heard of Ned and Dan Kelly until about five months afterwards, when the first sensational episode in the history of the gang occurred.

On October 25, 1878, a party of police consisting of Sergeant Kennedy and Constables Lonigan, Scanlan, and Mclntyre were despatched from Mansfield to establish a depot beyond the Wombat — if possible near Stringy Bark Creek — with a view to apprehending Ned and Dan Kelly for wounding Constable Fitzpatrick at the hut of the Kelly family at Greta.

The two Kellys were known to be in hiding somewhere in the ranges, but Kennedy had no knowledge of the immediate vicinity, or that the Kellys were accompanied by Steve Hart or Joe Byrne. He therefore took no precautionary measures against surprise. This neglect cost Sergeant Kennedy and Constable Scanlon and Lonigan their lives.

McIntyre, who had been left in charge of the camp, was suddenly surprised by Ned and Dan Kelly, Steve Hart, and Joe Byrne although the identity of the two latter was not discovered until some months afterwards, when the raid was made by the gang on the National Bank, at Euroa.

McIntyre had no alternative but to surrender, and the gang then awaited the return of the other three police. On their return about sundown, they were immediately fired upon from behind a fallen log by the gang, and a skirmish, lasting several minutes, took place, during which 30 or 40 shots were exchanged.

Scanlan and Lonigan were killed, and Sergeant Kennedy was wounded.

A Black Deed.

Here is said to have occurred the incident involving the darkest stains on the gang’s career. The ill-fated Kennedy, who had the reputation of being a good and brave man, pleaded hard with Ned Kelly, when wounded, not to be killed, but to be allowed to live to say goodbye to his wife and children. This request Ned Kelly refused, afterwards justifying himself on the ground that the sergeant was hopelessly wounded, and was better out of his misery.

During the excitement of the melee McIntyre managed to make his escape and gave the alarm.

The two Kellys were declared outlaws, and a reward of £500 each was placed on their heads, and also on those of their accomplices who were at the time supposed to be identical with John King and Terence Bourke.

The opinion was just beginning to gain ground that the desperadoes had cleared the country when the community was startled with the news that the gang had stuck up Younghusband’s station, near Euroa, a flourishing township about 80 miles from Melbourne, on the North-Eastern railway line, and after conveying all the occupants in the station’s vehicles into the township had held up the local branch of the National Bank, and carried away upwards of £14,600 in notes, gold, and specie, together with other valuable loot, on pack-horses.

It was during the course of this visitation that the identity of Steve Hart and Joe Byrne was established by a servant girl at one of the hotels where the occupants of the town were bailed up by two of the outlaws — Hart and Dan Kelly —while the bank was raided by Ned Kelly and Joe Byrne. The township had ever 200 inhabitants.

Meeting Kate Kelly.

The writer happened to be at a bush race meeting at a small place called Whoronly on the Ovens river in January, 1880, in the very centre of what was then known as “the Kelly country.” Kate Kelly, her sister, Mrs. Skillion, Mrs. Ambrose, Miss Lloyd and another young woman took part in a ladies’ race, and the event was won by Mrs. Skillion on a roan horse entered as Chancellor, said to have been the mount of Dan Kelly at the time of the subsequent capture at Glenrowan. It was asserted that on that occasion the gang were present and that two of them, Hart and Byrne, actually attended a dance held at the local Shire Hall the same night in disguise under the very eyes of the police, of whom there were several present. It was also an open secret that the different members of the gang were, on occasions, known to visit their relatives and friends in both Benalla, Wangaratta and neighboring town and that Ned Kelly and Byrne had on one occasion taken a trip to Melbourne to see the outsider, Darriwell, win his Cup.

Another Town Held Up.

The lax methods of the police next led to the holding up of Jerilderie, a town containing about 300 inhabitants. This most audacious and daring feat was performed by the gang about eight months prior to their capture at Glenrowan. The desperadoes first visited the police station and locked up the sergeant and three constables in the watchhouse cells in broad daylight.

Commandeering the police uniforms the gang proceeded to the bank and had no difficulty in securing the contents of the safes to the amount of some £16,000 or £17,000. They then rounded up all the inhabitants of the town and made merry. They did not seem in the least anxious to make a departure until their horses were well fed and rested.

This escapade induced N.S. Wales to supplement the reward of £4000 by the Victorian Government for the gang’s capture by another £4000, making £8000 in all.

Writer’s Personal Knowledge.

This had probably something to do in the matter of hastening the end. Rumors got about that there were traitors among those who had hitherto been sympathisers, and that even some of the outlaws’ relatives were not beyond suspicion.

In this respect I heard Ned Kelly tell Sergeant Steele, while under guard at the Glenrowan railway station, after his capture, that the man, Aaron Sherritt, shot by Joe Byrne at the woolshed two days previously, was not the only one suspected of harboring the police to effect their capture, and that several others had been marked out by the gang for a similar fate as that which befell Sherritt as an example to traitors.

No doubt from what Sergeant Steele subsequently told me Ned Kelly had good grounds for his suspicions, and had the gang remained any longer in the district, their ultimate capture was evidently close at hand.

After his conviction Ned made a statement of the final programme he had planned out. This was to first/visit Aaron Sherritt’s place at The Woodshed, near Bccchworth, and shoot Sherritt and any constables found concealed in his house, and then proceed across country to Glenrowan, about 20 miles away, and wreck the train containing police and black-trackers, which they felt certain would be despatched from Melbourne to effect their arrest. Their next plan would have been to have proceeded to either Wangaratta or Benalla, close handy, .and loot a bank, then break up and make an effort to leave Australia.

Ned Kelly Captured.

On Sunday, June 27, 1880, news reached Wangaratta from Beechworth that Aaron Sherritt, formerly a schoolmaster, and supposed confidant of Joe Byrne’s, had been shot dead in his hut at The Woolshed, a deserted mining town, on the previous night by Joe Byrne, who was accompanied by another member of the Kelly gang.

There were four armed police constables in the house at the time, but instead of facing the situation, as one would have expected, they crawled under the bed and placed two females (one of them Sherritt’s wife) before them for protection. This earned them ignominious dismissal from the force.

The Kelly gang lost no time in making their way to Glenrowan, where they arrived with their firearms and armor about 2 o’clock on the Sunday morning. Their first act was to knock up Mrs. Ann Jones, the licensee of the Glenrowan Hotel adjoining the railway, unload and stable their horses, and retire for a few hours’ rest. Before daylight they were up, and rounded up all the residents of the township, about 40 in number, and placed them under guard at the hotel. They then forced the platelayers, the Reardons) (father and son) and Cherry, to pull up the railway lines for about 40 yards at a point about 150 yards on the Wangaratta side of the line.

They then returned to the hotel and awaited the arrival of the expected train containing the police.

The writer, with ——— Hart (Steve’s brother) and one or two other residents of Wangaratta arrived on the last scene before 8 o’clock on the Monday morning in time to witness the capture of Ned Kelly.

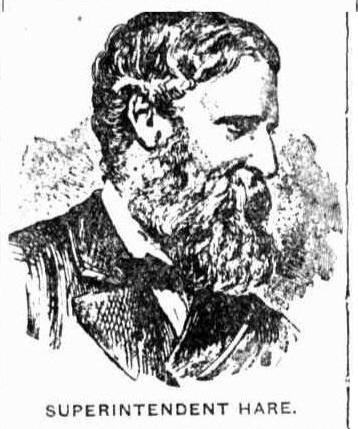

It was a beautiful clear, frosty morning when we arrived, and found the policmen firing volleys into the hotel from all angles — some ambushed behind trees, others lying down. Suddenly there was commotion from the rear in the vicinity of Morgan’s Look-out, and some members of the force were seen to suddenly spring up, throw away their rifles, and scamper for ambush.

Ned Kelly was the cause of the scamper.

It appears that he was the man who had shot Supt. Hare, although himself wounded in the arm badly. When he appeared close behind the rear line of police he was clad in a long light-colored macintosh coat, covering his armor, and armed only with a revolver. After shooting Hare he mounted his grey mare, to whom he was greatly attached, and got away towards Morgan’s Look-out; but it was not his intention to desert his companions in the hotel, and he returned on foot to fight his way to them.

He walked up coolly and slowly towards the police. His head, chest, back, and sides were all protected with heavy ¼in. armor, manufactured from plough mould boards.

When within easy distance of Constable Kelly he fired. The contest, then became one which almost baffles description. Nine police joined in the conflict, firing point blank, at Kelly, and it was apparent from the way that he staggered that many of the shots found a mark. Tapping his breast Kelly laughed derisively at his opponents as he coolly returned the fire.

For fully half an hour this strange contest was carried on, and then Sergeant Steele suddenly closed in on Ned, and within a range of ten yards fired two shots of buckshot from a double-barrelled breachloader gun into the lower part of the outlaw’s legs, which were unprotected. This brought Kelly down. Steele rushed in and the fight was at an end.

Mistaken Police Shot.

Shortly after 12 o’clock a young man named Reardon, wearing a white handkerchief, appeared at the rear of the hotel. Mistaking him for one of the outlaws one of the police party fired upon him and severely wounded him in the shoulder. This appeared to terrorise the occupants in the hotel, who refused to come out, although repeatedly called upon by the police to do so.

About. 2 o’clock, however, they suddenly rushed out of the front door, holding up their hands. The police ordered them to advance, but many of the unfortunate people were so terror-stricken, that they ran hither and thither screaming for mercy. Finally they approached the police and threw themselves upon their faces. One by one they were called upon, and having been minutely searched, were allowed to depart.

After this the police kept up a constant fire on the hotel where the bushrangers still were, but the fire was not returned. It was believed that Dan Kelly and Hart intended lying quiet until night, and, under cover of darkness, to make an attempt to escape. With a view of preventing that Superintendent Sadlier decided to fire the hotel and force the outlaws into the open.

Cannon to the Front.

A cannon had been sent for from Melborne earlier in the day, but it was feared that it would not arrive in time to be of use.

Just as the police were about to put their newly-conceived plan of incendarism into operation Mrs. Skillion and Kate Kelly, accompanied by Wild Wright, arrived on the scene. The females were attired in dark serge riding habits trimmed with scarlet, and jaunty hats adorned with conspicuous white feathers.

Father Gibney, of West Australia, who was present, tried to induce Kate to enter the hotel and ask her brother Dan and Hart to surrender. Kate spiritedly replied that, much as she would like to see her brother before he died, she would sooner see him burnt alive than ask him to surrender.

Under a barrage of heavy fire Constable Johnston set fire to the hotel.

Father Gibney volunteered to induce Hart and Dan Kelly to surrender. He walked to the front of the door, crossing himself on the way, and a few moments afterwards was followed by two constables. A shout of terror emanated from the onlookers as a mass of flame and smoke burst from the walls and roof of the building, and a few seconds afterwards the priest and police emerged bearing Martin Cherry, a railway platelayer, in a dying state, and the dead body of Byrne. The rescuers stated that when they entered the hotel they saw the bodies of Hart and Kelly lying in one of the bedrooms. When the building was completely demolished, amongst the debris two charred bodies were discovered. They were buried two days afterwards in the Wangaratta Cemetery, the coffins bearing the inscriptions:

STEPHEN HART,

Died June 28, 1880,

Aged 21 years.

DANIEL KELLY,

Died June 28, 1880,

Aged 19 years.

The inscription on Byrne’s coffin read:

JOSEPH BYRNE.

Died June 28, 1880,

Aged 23 years.

The End of Ned.

Ned Kelly was removed to Benalla by special train, thence to Melbourne after an affectionate parting with his sisters. And that was the end of Ned. He was hanged on November 11, 1880.

———